The genocide of the Herero and Nama

Between 1904 and 1908, about 80% of the Herero people and 50% of the Nama people living in the territory of present-day Namibia were exterminated by the forces of the Second Reich, , that is approximately 65,000 Herero and 10,000 Nama. In the process of being publicly recognized by the Federal Republic of Germany as genocide, this crime of African colonial history is today considered the first genocide of the 20th century.

In 1904, as a reaction to the rules imposed by the German colonial administration and the abuses and mistreatments of the colonists, a revolt broke out in South-West African Germany, today Namibia. The forces of the Second Reich repress it with brutality and defeat the Herero. An extermination order – issued by General Lothar von Trotha on 2 October 1904 – enjoined the Kaiser’s troops to kill indiscriminately, thus condemning men, women and children. The Nama in turn take up arms against the Germans and suffer the same fate as the Herero. In the concentration camps opened in 1905, such as those of Windhoek, Swakopmund and Shark Island, the prisoners Nama and Herero are eliminated by work and succumb to disease, maltreatment and malnutrition. Skulls of victims are then sent to Germany for racial scientific research.

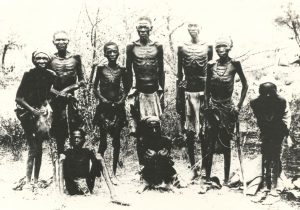

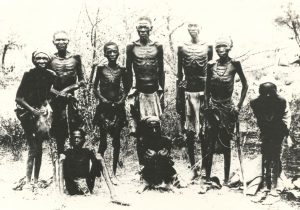

Emaciated Herero found in the desert. © Coll. J-B. Gewald / Courtesy of Vereinigte Evangelische Mission Archiv, Wuppertal.DR.

Beginnings

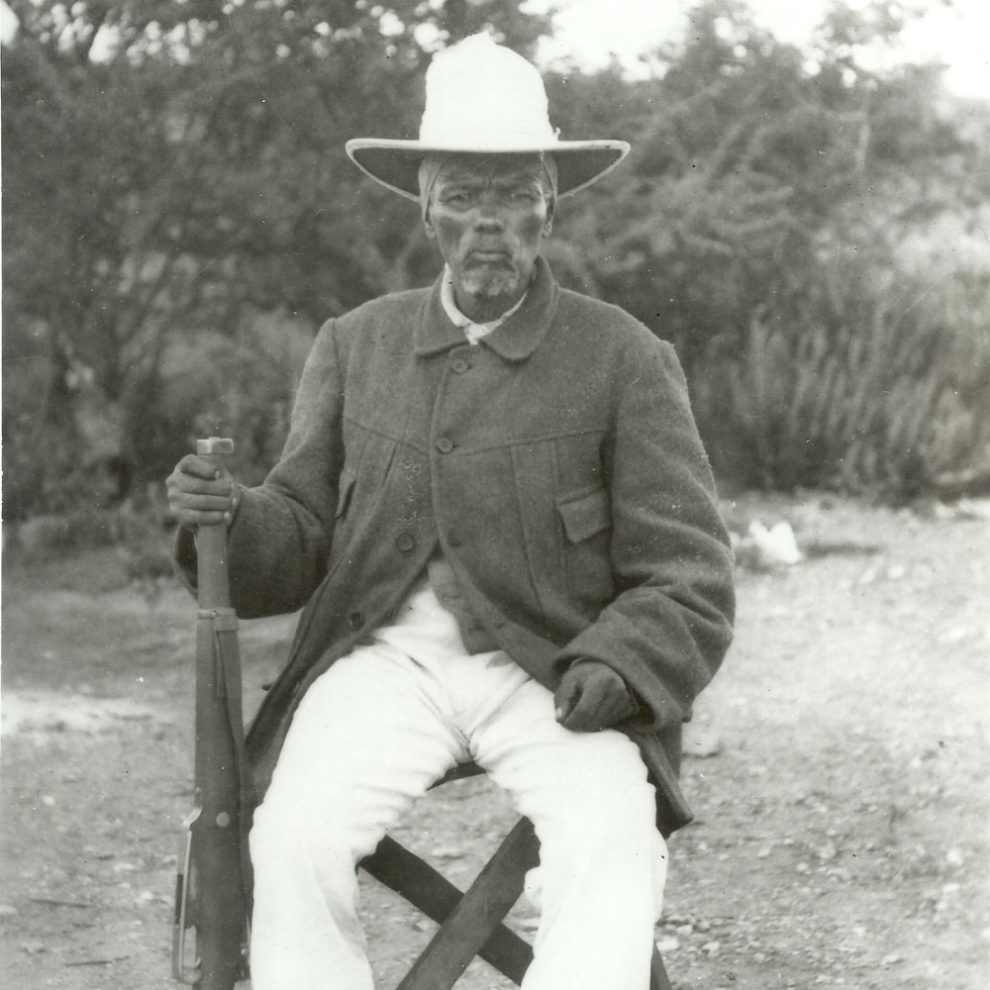

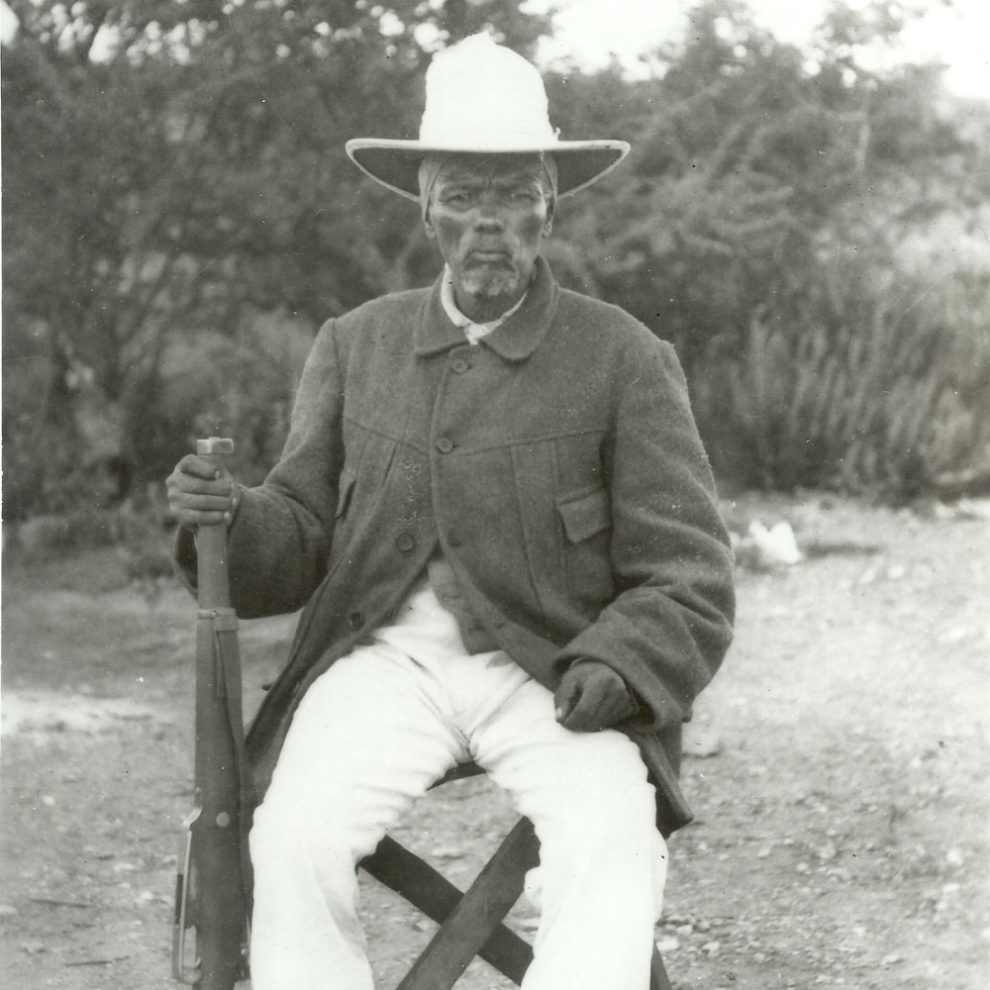

Hendrik Witbooi (circa 1830-1905). Rising to power in the 1880s, he became captain of the Nama Witbooi in 1888. © Coll. J.B. Gewald/ Courtesy of National Archives of Namibia.

In the middle of the 19th century, the peoples who lived in the region that now corresponds to central Namibia were the Herero, Nama, Basters, Damara, Khoisan and Ovambo. Around 1840, when the first Rhenish missionaries landed in the colony, most of central Namibia came under the control of Captain Oorlam Jonker Afrikaner and his herero vassals, Kahitjene and Tjamuaha.

Some herero chiefs ally with the missionaries in order to obtain protection and material goods; the missions then become important centers of commercial and diplomatic exchanges. With the disappearance of Afrikaner and Tjamuaha in 1861, the hegemony of the Oorlam collapsed and it was Tjamuaha’s son, Kamaharero, who then established himself as the most powerful of the generation of independent chiefs.

In the 1880s, incessant disputes over pastures degenerated into a prolonged conflict with Hendrik Witbooi, an educated and charismatic leader who managed to bring together the Nama and Oorlam clans in the South.

The protectorate of South-West African German is proclaimed on August 7, 1884. During the decade that follows, colonization struggles to establish itself: the financial gains are derisory and although the first governor, the high commissioner of the Reich, Heinrich Ernst Göring, appointed in 1885, succeeds in ratifying a «treaty of protection» with Kamaharero, the Germans cannot actually offer him any assistance against Witbooi. When Göring makes the unforgivable mistake of touching an ancestral burial place, Kamaharero, furious, cancels their agreement. In 1888, worried about his safety, Göring had no alternative but to leave the protectorate hastily.

“On all sides, terrible scenes were offered to our eyes. Beneath the hanging rocks rested the corpses of seven Witbooi who, in their agony, had crawled to the recess, their bodies pressed together. Elsewhere, the body of a Bergdamara woman blocked the path while children of three or four years old, sitting in silence, played next to her body. It was a frightening vision: burning huts, human bodies and animal remains, rifles destroyed and unusable, that was the picture we were presented with.”

In Kurd Schwabe [ German soldier in South West Africa, during the Hoornkrans massacre] Mit Schwert und Pflug in Deutsch-Südwestafrika E. S. Mittler, 1899.

Violence and loss of territory

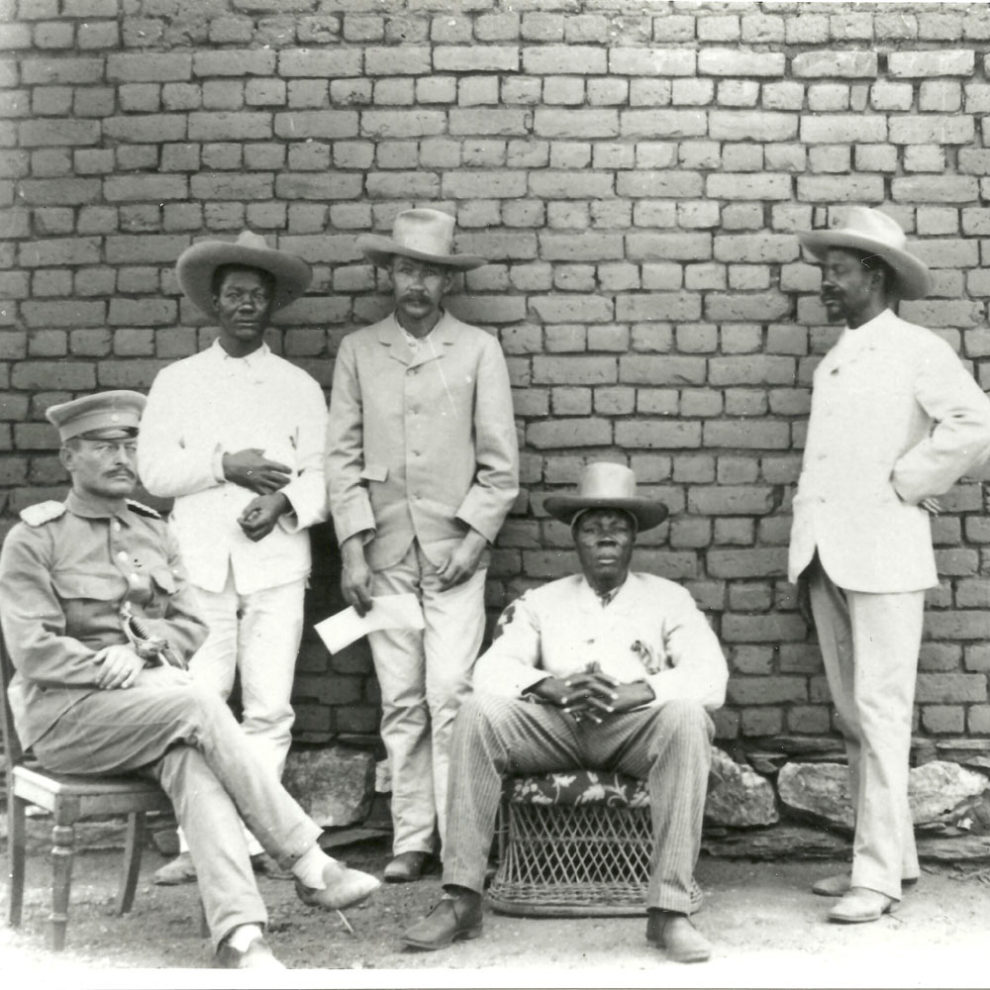

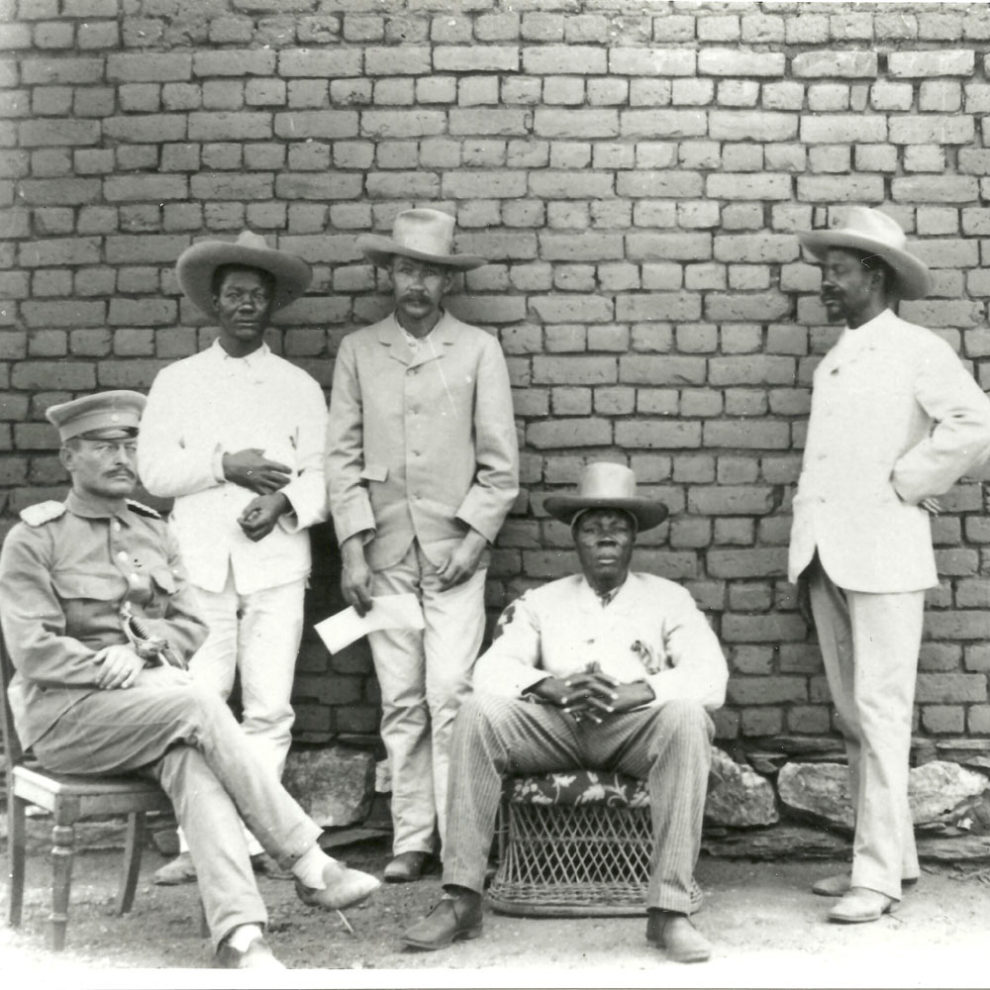

From left to right: Theodor Leutwein, Johannes Maharero or Michael Tjisiseta, Ludwig Kleinschmidt (performer of German and Nama ancestry), Manasse Tjisiseta and Samuel Maharero. Omaruru, 1895. © Coll. J.B. Gewald / Courtesy of National Archives of Namibia.

The first German troops arrive in the colony in the middle of the year 1889, led by Curt von François.

Samuel Maharero, son of Kamaharero, more and more disappointed by the attitude of Germans, and Hendrik Witbooi, who understands the magnitude of the colonial threat, ally. Faced with this unified front, von François launches, on the night of April 12, 1893, a surprise attack on the camp of Witbooi: the German troops massacre no less than 75 women and children. Despite this bloodbath, von François cannot subdue Witbooi.

In 1894, he is replaced by Theodor Leutwein, who takes back control by imposing the application of protection treaties. Samuel Maharero approaches Leutwein to extend his power. Defeated after a fierce thirteen-day battle, Witbooi must resolve to sign a treaty of collaboration with the Germans.

In 1896, the two chiefs fought alongside Leutwein against the Mbanderu and the Khauas Khoi: it was the first of many campaigns conducted against the «rebel tribes» with the dual aim of extending Maharero’s influence and liberating lands, livestock and labor for German settlers. The survivors of the fighting are systematically sent to forced labor while the land and cattle of the Herero pass into the hands of the Germans. When rinderpest strikes the overpopulated territories left to the Herero, the economic and social consequences are catastrophic. At the end of the decade, the Herero lost their independence.

The warrior fever

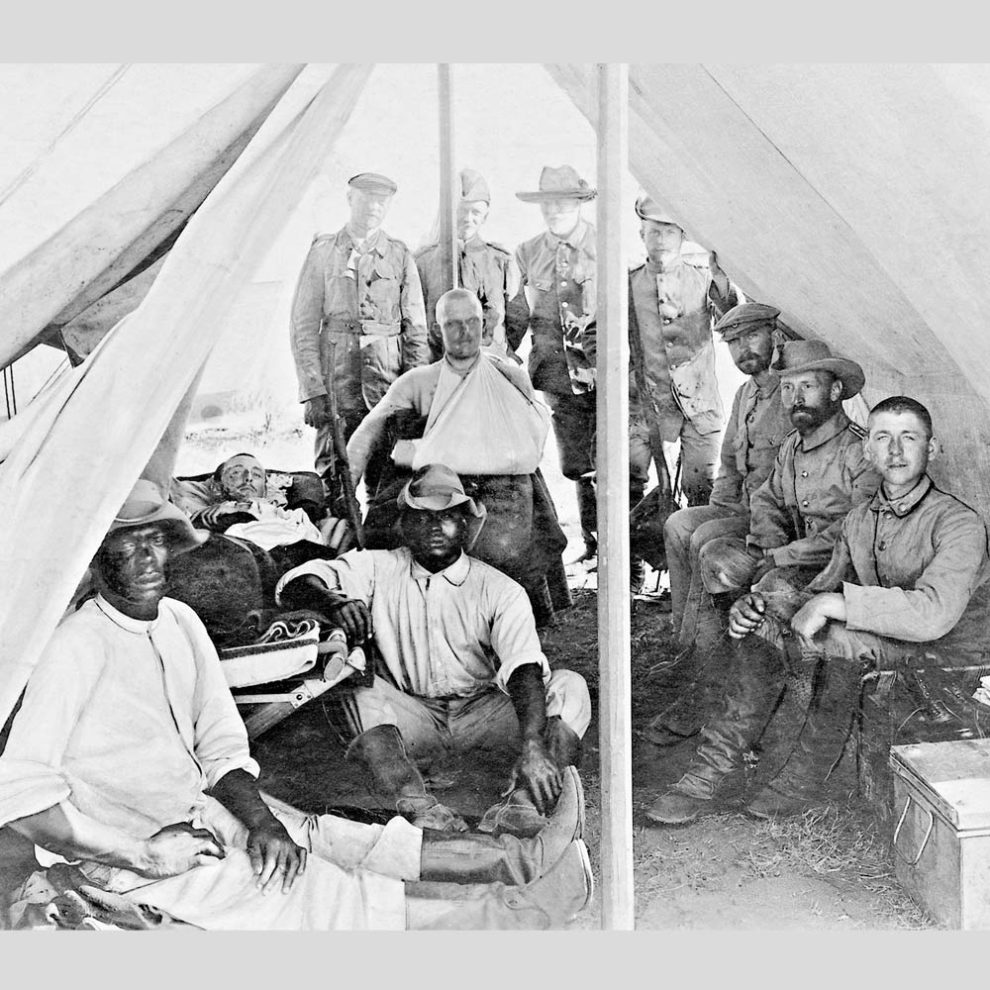

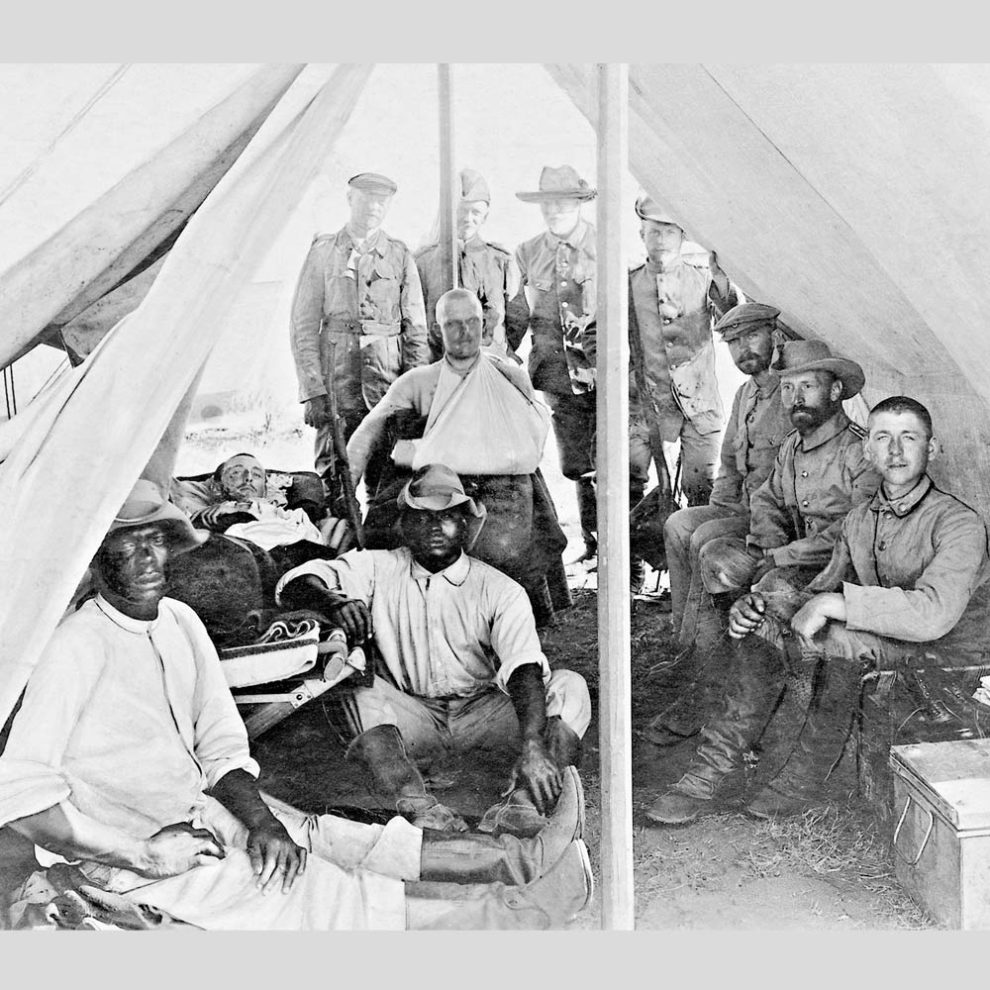

Soldiers of the protection force during the war against the Herero. Photograph taken after the Battle of Owikokorero between the German troops led by Lieutenant Franz Georg von Glasenapp and the Herero led by Tjetjo, 13 March 1904. The Germans suffered heavy losses during this battle. © Bridgeman Images.

Despite the efforts made by the herero chief Samuel Maharero to consolidate his alliance with the Germans, abuses are increasing. German officers indulge in rapes, beatings and murders of Africans with impunity.

In Okahandja, Lieutenant Ralph Zürn does not hesitate to forge the signatures of the herero chiefs to appropriate land and even to exhume skulls as a source of additional income.

On January 12, 1904, while the German troops are busy trying to put down the "rebellion" of the Nama Bondelswarts in the South, the Okahandja Herero, exasperated by the injustices committed by Zürn and the continuous loss of territory, attack the German farms, to the businesses and the colonial infrastructure. These attacks lead to a brutal repression by soldiers and settlers who engage in indiscriminate acts of lynching and retaliation.

In Germany, following the exaggerated descriptions of these aggressions, a real war fever develops. As violence spreads, the local uprising turns into a major conflict, forcing Maharero to side with the "rebels". To the great displeasure of the politicians in Berlin, his men initially succeeded in resisting Leutwein’s troops using guerrilla techniques.

Leutwein was relieved of his command and replaced by the ruthless general Lothar von Trotha who landed in the colony in June 1904 with thousands of men. Unlike his predecessor, who had hoped to end the conflict through diplomacy, von Trotha is determined to put an end to the Herero. From the general’s point of view, war with the Herero is inevitable and will allow the achievement of white domination in the colony.

Me, great general of the German troops, I am sending this letter

to the Herero people. The Herero are no longer German subjects. They killed and stole, they cut off the ears, nose and body parts of wounded soldiers, and now, without any cowardice, there is no more desire to fight. I say unto the people: whoever delivers a captain shall receive 1000 marks, and he who delivers Samuel shall receive 5000 marks. The Herero people must, however, leave the territory. If the populace does not comply, I will force them to do so using the Groot Rohr (cannon). Within the German borders, every Herero, without or with a weapon, with or without cattle, will be shot. I will no longer accept women and children from now on, I will send them back to their people or let them be slaughtered.

Here is my statement to the Herero people.

The great general of the powerful German Kaiser.”

Extermination order, 2 October 1904, signed by Lothar von Trotha.

The order of destruction

Fire at the encampment of Captain Nama Simon Kopper. © Coll. J-B. Gewald / Courtesy of National Archives of Namibia.

When General Lothar von Trotha landed in the colony, the majority of the Herero, nearly 50,000 men, women and children accompanied by their flocks, gathered under the command of Samuel Maharero on the Waterberg plateau. Anticipating negotiations, they stopped their attacks. Von Trotha however has no intention of negotiating. His troops encircle the Waterberg camp and, at dawn on August 11, 1904, they attack with orders not to take prisoners.

Yet, the Herero manage to break the encirclement and tens of thousands of them flee into the desert. Von Trotha orders that they be pursued, while sealing the territory and cutting off access to water points. For weeks, pushed further and further into the desert, countless Herero die of dehydration.

On 2 October 1904, the general issued a destruction order, the Verbri ungsbuffs, which declared that any Herero present on "German territory" would be shot.

German soldiers, exhausted, sick and whose racial hatred was fueled by rumors of Herero cruelty, massacre civilians, including Herero who did not take part in the war. When the order is lifted following the intervention of the missionaries, the genocide enters a new phase: the Herero survivors are incarcerated in concentration camps and forced to do forced labor.

Some herero fighters manage to join the Nama from the South. Hendrik Witbooi, who brought troops to reinforce the Germans at Waterberg, ended up two months later turning against his allies. Aware of the desire that drives settlers to disarm and control all Africans, the Witbooi and their Nama allies open hostilities by attacking European farms as well as their convoys, killing men and seizing everything of value. Follows a painful guerrilla war that will last four years.

The Nama use their knowledge of the terrain to attack the German forces who continue to perpetuate their atrocities. On April 23, 1905, von Trotha made a declaration that threatened the Nama with the same fate as the Herero, but he failed to subdue them before his departure on November 19, 1905.

After the death of Witbooi following an injury received on the battlefield near Vaalgras on October 29, 1905, other captains, among them Cornelius Fredericks of Bethany, Simon Kopper of the Nama Franzmann and Jakob Morenga, a charismatic leader of mixed descent, herero and nama, continue the fight. The latter is finally shot by the police of Cape Cernés. Fredericks and his men are forced to surrender in March 1906. They are all interned in the notorious concentration camp: Shark Island – the island of sharks.

The concentration camps

Herero women doing laundry in the Swakopmund concentration camp. Around 1906. © Coll. J-B. Gewald / Courtesy of National Archives of Namibia.

Following the brutal campaign of General von Trotha, the colony is faced with a severe lack of manpower. Herero prisoners – men, women and children – are then interned in concentration camps and used as forced workers, notably in the construction of the new railway.

Friedrich von Lindequist, governor of the colony from November 1905 to August 1907, calls on all the Herero to surrender and join the assembly camps of Omburo or Otjihaena, from where they are escorted to the railway work centers, or in concentration camps such as those of Windhoek, Swakopmund or Lüderitzintercept.

The living conditions in these camps are terrible. The prisoners have only improvised shelters, devoid of sanitary facilities. Young girls are regularly raped. They are several thousand to perish from abuse, malnutrition, and diseases. The decrease in the number of prisoners is blatantly evident in the monthly reports kept by the district authorities, who carefully record both employable (arbeitsdent) and unemployable (unapte).

The war officially ends on March 31, 1907, but the camps will not be closed before January 27, 1908. When the Nama lay down their arms, they in turn are interned in concentration camps. In September 1906, von Lindequist decided to transfer 1,700 prisoners nama to the camp on Shark Island, near the port city of Lüderitz, where the mortality rate was exceptionally high. Some 2,000 Herero are already interned there, suffering from the cold, lack of food and abuse. When the Nama arrive, already weakened by the forced labour to which they have been subjected in the North, their state of health deteriorates rapidly. Despite the protests of the missionaries, the older men, women and children are systematically enlisted in the construction of a dock in the port of Lüderitz until death follows.

Mid-February 1907, the high mortality rate of the Nama (70%), leads to the abandonment of work; among those who are still alive, one third is so sick that it is likely to disappear very soon.

When the camps were closed in 1908, the colonial authorities, still fearing the potential guerrilla of the Nama, decided not to release them. In 1910, years after the end of the conflict, a group of 93 Nama Witbooi and Nama, including women and children, were deported to another German colony, Cameroon, where most disappeared, carried away by forced labor and tropical diseases.

Racial inequality

Young Africans (Basters) (original title), Bethany, 1897. The first German settlers often married young girls from the Christian community of the Basters of Rehoboth, of Khoisan and European descent, considered European by their appearance and customs © BPK, Berlin, dist. RMN-Grand Palais/BPK image.

The majority of settlers who seize land and livestock from the Herero treat Africans with a total lack of respect. Rape is frequent, exacerbated by the shortage of German women. Fears of racial degeneration among the German people (Volk) finally led to the prohibition of mixed marriages on September 23, 1905. The notions of racial difference are based on late 19th-century German anthropology, which made a distinction between so-called "civilized" peoples and others considered as "primitive". It was hoped to understand the human race through objective observation of so-called "primitive" peoples such as those exhibited in human zoos, very popular in Europe at the time. One of the most spectacular of these events is undoubtedly the Colonial Exhibition which takes place in Berlin: more than a hundred people from the German colonies are exhibited there in the park of Treptower during summer 1896. Samuel Maharero, considering that it is a unique diplomatic opportunity, sends five notables, among whom his own son, Friedrich Maharero, so that they can meet Kaiser Wilhelm II and consolidate their alliance with the Germans. The search for objective data in order to establish the characteristics of each type led to a real collective frenzy which was going to drain in its wake a macabre trade of human remains.

The collection of human remains

Until 1904, the collection of human skulls for anthropological research was not organized. In Berlin, scientists have little control over the specimens that arrive in their collections, often "souvenirs" or trophies brought back by soldiers returning from the colonies. The concentration policy of von Lindequist allows for systematic collection. The military doctors serving in the camps receive requests from Berlin scientists who ask them to keep skulls and entire heads of Nama and Herero. There is no doubt that Dr. Bofinger participated in such activities at Shark Island. Scientists undertake to prove the hierarchical difference between Europeans and Africans, among them are the researchers of the Pathological Institute of Berlin who receive, between 1906 and 1907, an indeterminate number of heads nama and herero coming from the colony. The manipulation of the results confirms the racist stereotypes prevalent in Germany and justifies the racial laws established in the German South-West Africa. Among the published studies, that of Eugen Fischer (1913), who intends to demonstrate the negative consequences of racial diversity within the Basters of Rehoboth, remains the most influential.

« Do you know a way to acquire a large number of herero skulls? The skull you gave us corresponds so little to the images made so far from problematic and inferior material that it seems necessary to me to obtain a larger collection of skulls for scientific research and rather quickly if possible.

Letter from the anthropologist Felix von Luschan to Ralph Zürn, lieutenant stationed at Okahandja at the beginning of the uprising on June 22, 1905. Upon his return to Germany, Zürn brings with him herero skulls as a souvenir that he will donate to von Luschan.

A model colony

Reproduction of the cover of «Kolonie und Inness» (the colony and the native land). The magazine describes the ideal German settler in this way: a man who is not afraid of work and who carries a bit of the devil inside him, is the ideal man for our Southwest. © Deutsches Historisches Museum, Berlin/ I. Desnica

While the Herero and the Nama are incarcerated in concentration camps, their lands are confiscated: since 1882, the German government has appropriated nearly 46 million hectares.

In 1913, the colony counted nearly 15,000 individuals, including many former soldiers. It can claim to have its own racetrack and a cinema as well as an extensive railway network built by forced labour. As the local economy boomed, especially after the discovery of diamond mines near Lüderitz, the state responded to the labor shortage by tightening its system of racial control.

From 1907, all Africans over seven years old must wear numbered passes (copper tokens) that assign them a specific region of work, while the Herero are forcibly distributed as workers among the settlers. The system is not flawless, however, as the territory is too large to allow the strict control hoped for. African workers are regularly beaten and often dismissed.

The precarious prosperity of the colony is short-lived: in February 1915, during the First World War, the South African forces invade the territory. On October 21, 1915, the German South-West Africa passes under a British mandate.

The Blue Book

In order to ensure the definitive confiscation of theformer German colony, the British Imperial War Cabinet decides to gather and publish the evidence of atrocities committed by the Germans in South West Africa.

From September 1917, Major Thomas O'Reilly produced a compilation containing translations of German documents, to which were added the sworn statements of witnesses (Africans) and survivors, accompanied by photographs. This compilation is published in a Blue book, that is to say a report from the British government. Although the document clearly serves the interests of the Crown, it has been accurately produced and remains to this day a reliable source that includes priceless tales of Herero and Nama about the genocide perpetrated by the Germans.

A past present forever

Captain Hendrik Samuel Witbooi Jr., great-grandson of Hendrik Witbooi, celebrating Heroes Day, 1989. Witbooi Jr. (1934-2009) was an important member of SWAPO and was Deputy Prime Minister of Namibia between 1995 and 2004. © Henning Melber / Courtesy of Reinhart Kößler and Joachim Zeller.

In the context of a policy of "reserves", the Nama and the Herero recover some lands and a certain autonomy. In the meantime, the Herero and the Nama are working to rebuild their community identity around commemorative events. The funeral of Samuel Maharero, who died in exile and was buried in Okahandja on 26 August 1923, is a spectacular event. The event has been commemorated every year since then under the name of Red Flag Day or Herero Day. On the side of the Nama, the inauguration in the thirties of the memorial stone dedicated to Hendrik Witbooi marks the first Witbooi Day, an annual commemoration punctuated by reconstructions of battles and political speeches.

In 1960, the national liberation movement of the people of South West Africa (SWAPO – Organization of the People of South West Africa) was born and the struggle for independence intensified. On 21 March 1990, Namibia becomes independent and the SWAPO government, under the presidency of Sam Nujoma, begins to review the policy of remembrance as part of a national reconciliation. A new national monument inaugurated in 2002, the Heroes Acre, is designed to symbolize the birth of a modern state, fruit of the armed struggle against colonialism. However, it was not until 2013 that the Reiterdenkmal, the greatest symbol of German colonial power, was withdrawn.

While the government focuses on nation-building, the Nama and the Herero demand an apology and ask reparation to the German governmentfor the atrocities committed and the incessant injustices: the majority of profitable farms are still in the hands of white farmers.

In 2001, Herero led by the grand chief Kuaima Riruako file a complaint against the German government in the United States. Although this complaint was dismissed, the compensatory claim is fueled by partial apologies made in 2004 and by the repatriation of the remains of Nama and Herero victims of the genocide.

Finally, in July 2016, the German government announces that an official apology is about to be presented – an important step in the long process of accepting the painful past of the Nama and Herero, Namibia and Germany.

If you wish to discover other resources on the subject (vintage press, bibliography, questions to specialists) click on the link below.

RESOURCES