The co-edition Calmann-Lévy

Discover the latest works from the Mémorial de la Shoah collection published by Calmann-Lévy, on sale at the Mémorial bookshop or on the online bookstore.

Treblinka, 1942 – 1943: a factory producing Jewish deaths in the Polish forest of Michal Hausser-Gans

" Auschwitz was nothing [after Treblinka], Auschwitz was a holiday camp."

Thus expressed Hershl Sperling, one of the very few survivors of the most appalling killing center of the Operation Reinhard. His statement may seem sacrilegious to the reader who is uninformed about the reality of Treblinka. Indeed, if the name of this site is known, its history, like that of Belzec and Sobibor, is much less so, the Nazis having taken great care to erase the traces of their barbaric enterprise, to liquidate the last witnesses and to raze the vestiges they had abandoned. Hence the challenge posed by this 'impossibility of accountability'. Thus, in 1943, the site of Treblinka had already taken on the appearance of a farm.

Last stop of a black path drawn from Berlin, Treblinka, among all the killing centers, outperformed Auschwitz in efficiency. It is there that the destruction of the Jews was the most 'expeditious': nearly a million people were murdered in 400 days. Based on unpublished sources, Michal Hausser Gans describes in detail, since its genesis, the functioning of the camp, highlighting the transformations undertaken to perfect the death machine. Until the revolt of August 2, 1943, reported by some of the survivors who, against all odds, managed to seize the machine of this insurmountable model of genocidal industry. This exhaustive study makes it possible for the first time to make accessible to a wide audience the confrontation with "the worst of the worst" and with this journey towards the horror that Europe failed so long to decipher.

No right, nowhere: journal of Breslau 1933 – 1941 by Willy Cohn

Historian, Willy Cohn is one of the major intellectual figures of Jewish Breslau between the two wars. Preoccupied by the course of things since the advent of Hitler, Willy Cohn is for his descendants, as for posterity in the broad sense, the chronicler of the destiny of the Jews and Judaism before what he presides to be the end of a world, his own and that of his family.

Historian, Willy Cohn is one of the major intellectual figures of Jewish Breslau between the two wars. Preoccupied by the course of things since the advent of Hitler, Willy Cohn is for his descendants, as for posterity in the broad sense, the chronicler of the destiny of the Jews and Judaism before what he presides to be the end of a world, his own and that of his family.

He therefore devotes all his strength, until the last hours before his deportation, to write and makes sure to put back in a safe place a testimony that proves exceptional. He does it as a historian, who records the restrictions of rights, dispossessions, deprivations; as a German Jew, who desperately cares about the Germany for which he fought during the First World War; as a pious man who believes in the strength of Jewish history, he shares the contradictions that undermine him, his hesitations about what to do: flee or not, what to do in Palestine? He had neither the time nor the means to leave and was assassinated with his second wife and their two daughters in Kaunas in Lithuania, while his first wife was gassed at Auschwitz.

With this abridged version, the Breslau Journal presented here delivers us a valuable document, which the German press compared to the testimony of Victor Klemperer, and which had an immense impact at its publication. It makes us take an exemplary measure of what was the programmed destruction of the Jews in Europe under Nazism.

Born in 1888 in Breslau, then a city of the Reich, (today Wroclaw in Poland), Willy Cohn teaches history at the high school and dedicates himself to research on the history of Sicily during the Norman era. His works are still a reference today. Politically engaged, he notably writes biographies on Marx, Engels, Lassalle, and writes articles on Jewish history. He also left Memoirs.

“VICHY, THE FRENCH AND THE SHOAH – A STATE OF SCIENTIFIC KNOWLEDGE”

(Review of the History of the Shoah, No. 212, ed. Memorial of the Shoah, October 2020)

under the direction of Laurent Joly (CNRS)

under the direction of Laurent Joly (CNRS)

For its second issue emanating from the new editorial committee led by Audrey Kichelewski and Jean-Marc Dreyfus, RHS – Revue d'histoire de la Shoah, the oldest scientific journal on the subject, testifies to the vitality and richness of international research on the Shoah. In 1945, faced with the purge, the leaders of Vichy, Pétain and Laval the first, had thus justified their policy against the Jews: Vichy avoided to the Jews of France the fate of the Jews of Poland; its policy was guided by the desire to protect the French Jews, even if it means sacrificing foreign Jews to change; and it is thanks to this policy that the majority of Jews have survived in France...

Oneg Shabbès, Warsaw Ghetto Newspaper by Emanuel Ringelblum

(Translated from Yiddish by Nathan Weinstock and Isabelle Rozenbaumas)

(Translated from Yiddish by Nathan Weinstock and Isabelle Rozenbaumas)

Emanuel Ringelblum and some Jews from the Warsaw ghetto set up an information and document collection team that meets every Saturday under the name ofOneg Shabbat (Oneg Shabbes in Yiddish), "the joy of the Sabbath." At the same time, Ringelblum keeps a diary, written in Yiddish. Over the months, the description of the dreadful misery organized by the Germans takes over. The description (and the cold anger that accompanies it) of the treason of a part of the Jewish ruling classes, of the baseness of many, of the treachery of a handful also imposes itself. But the author also highlights the solidarity and the vitality of cultural resistance to this martyrdom. The present translation of this manuscript found at the Liberation includes all the daily chronicles of Ringelblum.

Journal 1943-1944 by Leïb Rochman

Journal 1943-1944 by Leïb Rochman

(Translated from Yiddish by Isabelle Rozenbaumas, ed. Calmann-Lévy/coll. Memorial of the Shoah, February 2017)

Leïb Rochman (1918-1978), the author of the masterpiece À pas aveugles d'un monde, wrote his Journal between 1943 and 1944 while he (over) lived hidden with his wife, his sister-in-law and two friends behind a double partition in the farm of a Polish peasant, then in a pit dug in a stable. Leïb Rochman and his companions hear the outside world, in particular their host’s conversations with neighboring villagers who deplore not finding any more Jews to be delivered to death in exchange for a few kilos of sugar. In addition to its literary beauty, this testimony is one of the most powerful stories about the Shoah in the Polish countryside.

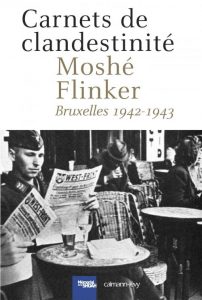

Notebooks of clandestinity – Brussels, 1942-1943 by Moshé Flinker

Notebooks of clandestinity – Brussels, 1942-1943 by Moshé Flinker

(Translated from Hebrew by Guy Alain Sitbon, ed. Calmann-Lévy/coll. Mémorial de la Shoah, February 2017)

At 16 years old, Moshé Flinker leaves the Netherlands with his parents and six brothers and sisters to escape Nazi persecution. Arrived in Brussels, he begins to write his diary in Hebrew. Well-versed in Jewish history, with a deep faith, his writings are driven by the conviction that the creation of a Jewish state on ancestral land is the only possible response to an attempt at extermination unique in history. His Diary ends on 19 May 1943 with these words: 'I feel like I am dead. Here I am.' On 19 May 1944, he was deported to Auschwitz and disappeared in Bergen-Belsen in January 1945.

(Translated from Yiddish by Nathan Weinstock and Isabelle Rozenbaumas)

(Translated from Yiddish by Nathan Weinstock and Isabelle Rozenbaumas) Journal 1943-1944

Journal 1943-1944 Notebooks of clandestinity – Brussels, 1942-1943

Notebooks of clandestinity – Brussels, 1942-1943